Introduction and Motivation

Before diving directly into CUDA powered simulations we can take a look at a simple approach to galaxy simulation to introduce the physics of collisions clearly. We can also quickly demonstrate the leapfrog algorithm which is a low order yet effective integration method for the motions of bodies under a force like gravity.

Motivation for these and further computational approaches in astrophysics is quite prevalent; predicting the conditions necessary for some of the more extravagant galactic collisions to form, predicting and fitting dark matter, and modelling the expansion of the universe on larger scales (should you have access to a cluster / supercomputer that is).

Collisions and Tidal Forces

A quick case study looking at the popular Mice Galaxies lets us study phenomena of colliding bodies, such as the formation of the tails you see below.

As described in the Toomre & Toomre paper we can observe the formation of a “bridge” between the two galaxies which will allow for the exchange of mass during passing, as well as the formation of elongated “tails” of stars which have been flung out from their respective disks. These qualities are found by Toomre & Toomre to be dependent on many qualities of the encounter:

“Good” (thin and dense) bridges form from tilted inclines of approach Long tails form best when the masses of the two galaxies are nearly one to one Formation depends heavily on the class of approach; parabolic, hyper… etc. Ribbon like features such as the upper left are typically 3 dimensional looping tendrils which are being viewed at an angle to appear as a 1 dimensional tail. In general the tails are formed by Tidal Forces, the same which the moon inflicts upon the earth, which become very expressive during the closest points of passage. In those moments which are highly dependent on the relative spins of the galaxies (which I will demonstrate in the simulations) the tails from each galaxy are violently whipped out as a result of the gradient of force the galaxies exert on each other.

Methodology - Leapfrog and Restricted Model

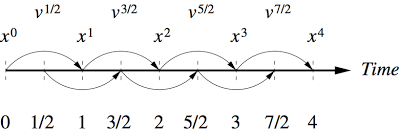

In order to integrate many object interactions through time we have to use some numerical approximation, as a true continuous integral would of course take forever on a computer. My approach has been to use the “Leapfrog” method, which is known to be extremely accurate for low time steps, and conserves angular momentum and energy perfectly. If there is interest, a common alternative is a Runge-Kutta or RK4 method, which will yield accurate results with larger time-steps and is attractive for this reason.

The Leapfrog Algorithm

As I’ve implemented it:

For all bodies in the system at once:

-

Determine the acceleration a body should experience given all other bodies

-

“Kick” the velocity of the body for half of a timestep

-

“Kick” the position of the body for a full timestep (using the half updated velocity)

-

“Kick” the velocity of the body for the next half timestep

This describes one timestep of the algorithm, which can then be run for however long is necessary. In the limit where you choose an infinitely small timestep you approach a continuum solution, however you don’t need to get close to this limit to achieve accurate results in many cases.

The Restricted Galaxy Model

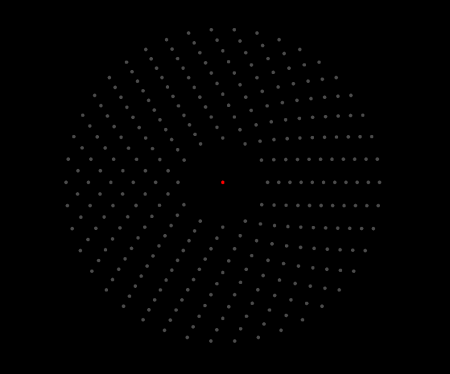

As mentioned before, we first want to demonstrate formations of tidal tails with a simple simulation which could run on any platform in reasonable time. To achieve this I have recreated the restricted or “toy” model of galaxies which is detailed in the Toomre & Toomre paper. Here’s what we are looking at:

-

The galactic disk is modeled as 11 concentric rings of massless points

-

Points are chosen simply to fill space and display interactions during the collision

-

Set to orbit the only massive object at the center, which makes up the entire mass

This model works surprisingly well as our galaxies are axially symmetric, and makes computation extremely simple with only two massive objects to use for acceleration calculation, which is N2 in time complexity using the most straightforward method and so limiting massive objects in this way is good for us.

Simulation and Results

Following the paper’s set of initial conditions, which includes various sets of tilts for the two disks, and putting them on the prescribed elliptic orbit which the paper suggests gives the results closest to reality, all that is left is to choose the relative spins of the galaxies, which turns out to be quite important! As it turns out, galactic tails like the ones exhibited by the Mice only arise during prograde collisions as opposed to retrograde. What this means is that the rotation of either galaxy is opposite that of the other upon collision, causing the “fringe” stars of either galaxy farthest from the center of collision to experience an additive force and be flung out.

Here I’ll show the resulting simulations of both prograde and retrograde approaches:

The retrograde approach ends up with what would be the tail “suns” getting their own momentum cancelled somewhat by the incoming galaxy, which does not match the spin of the representative point (thus “retro”-grade). The result is a jumbled distortion of the rings of each galaxy as their different orientations and the passing of a massive object throws everything off of their circular orbits. We can see the opposite of this effect, an additive force, in the prograde approach below:

We can tell that the proper tails have been formed from an elliptic and prograde collision, all that is left for me personally is to compare my results to Toomre & Toomre’s paper before moving on to a larger scale simulation.

We can compare the galaxies of the paper and my own simulation to our view of the real galaxies, all at the appropriate viewing angle which yields the famous “long line” of a tail.

Although a rotation is in order for the sky-view we can easily see why this simulation argues for the particular set of initial conditions to have resulted in what we see of the collision.

Conclusion

The restricted model has provided a good way to introduce anyone to the methodology at hand for n-body simulations (in particular our leapfrog method) as well as demonstrate a recreational ability from a simulation with very few parameters.

In the next post I will be demonstrating disk-bulge-halo galaxy simulations with tens of thousands of “stars” all of which will be massive, which is made computationally possible on my measly laptop by performing tasks in bulk and in parallel with NVIDIA’s CUDA platform.

References

-

On restricted galaxy simulations, and the Mice: Toomre & Toomre - 1972

-

A quick rundown of the leapfrog algorithm: The Art of Computational Science

-

The code I’ve used for the simulations can be found on my GitHub